In 1984 the young virtuoso Anne-Sophie Mutter made her first recording of the work, conducted by Herbert von Karajan – who insisted strings should sound rich and sustained in Baroque music just as in Brahms. The earliest taping still available was made by violinist Louis Kaufman and the strings of the New York Philharmonic in 1947 – it sounds robust but pretty unsubtle, too. Performances of Baroque music have transformed beyond recognition since the first recording of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons in 1942. Those musicians have never lost their appetite for a rapid ramble through the earth’s meteorological cycle courtesy of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. No wonder musicians talk of the intense imagination and character required to bring these concertos off. In ‘Spring’ he asks the solo violin to play like “il capraro che dorme”(the sleeping goatherd) and the viola like “il cane che grida” (the barking dog). In the same concerto, the soloist and lower strings conjure what one Vivaldi expert has called ‘fireside warmth’ while violins depict icy rain falling outside.Īdded to that are Vivaldi’s verbal instructions to the players. Just listen, in the final movement of ‘Winter’, for Vivaldi’s portrayal of a man skidding across ice using descending octaves on the second violins and violas. When it came to the detail of those occurrences – barking dogs, drunken dancers, buzzing insects – Vivaldi delivered elegance and originality where other composers had barely moved beyond crude animal-noise clichés. The structural thinking behind Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons was that each movement – twelve in all (three per season) – would establish a certain mood, against which narrative events could then play out. Where Vivaldi undeniably did succeed was in his successful exploration of compositional techniques – those that made The Four Seasons. Programme music hasn’t exactly been welcomed into composition’s hallowed sanctuary with open arms, despite the best efforts of Haydn, Beethoven, and Richard Strauss. With his elevation of descriptive music, Vivaldi ignited a debate that lasted for centuries and saw the art of telling stories through wordless sounds criticized by those who believed music should transcend earthly description. With his unequaled gift for orchestral color and melody, if anyone could do it, Vivaldi could. Vivaldi was determined to prove that descriptive music could be sophisticated, intricate, and virtuosic enough to be taken seriously – and that it could advance the cause of the concerto at the same time. So-called ‘programme music’ existed before, but it was seen by some as inferior and regressive. Vivaldi had set himself quite a challenge, but he’d also hit upon an idea that a lot of music theorists didn’t like. In these seemingly polite and pretty works, the composer opened a philosophical can of worms that continued to brim over with wriggling controversies for centuries. The Four Seasons had the theorists frothing too. And it wasn’t just the concert-going folk of northern Italy who experienced Vivaldi’s stylistic shot-in-the-arm. They might not have provoked a riot but, when Vivaldi’s Four Seasons were first heard in the early 1720s, their audience hadn’t heard anything quite like them before. Like those other seismic cultural milestones, Vivaldi’s most popular concertos also changed the course of musical history.

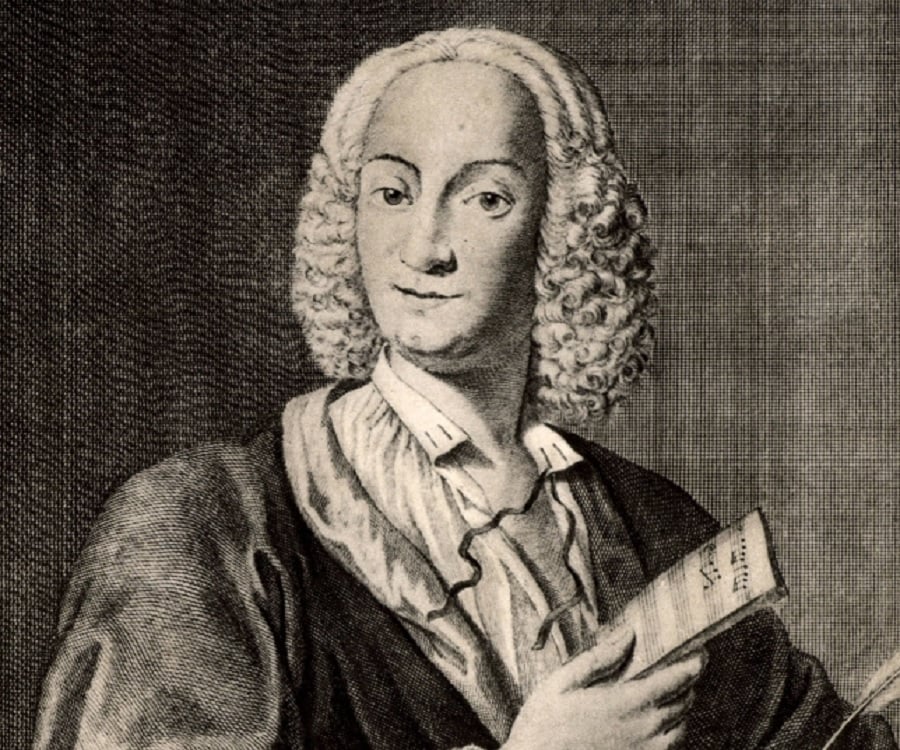

Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Beethoven’s Fifth… and yes, Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. The Four Seasons: A Guide To Vivaldi’s Radical Violin Concertos Listen to our recommended recording of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons performed by Janine Jansen now. Our guide to Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons analyses the secret of the concertos’ runaway success and explains why this now-familiar music was so radical for its time. The four violin concertos broke new ground with their programmatic depiction of the changing seasons and their technical innovations. Vivaldi’s best-known work The Four Seasons, a set of four violin concertos composed in 1723, are the world’s most popular and recognized pieces of Baroque music. He introduced a range of new styles and techniques to string playing and consolidated one of its most important genres, the concerto. Antonio Vivaldi’s influence on the development of Baroque music was immense.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)